Introduction

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) needs lengthy treatment with second-line anti-TB drugs, but these drugs are less effective and more toxic than first-line anti-TB drugs for drug-susceptible TB [

1]. As a result, the treatment outcomes of patients with MDR-TB are usually not satisfactory. In 2018, the treatment success rate for MDR- and rifampicin-resistant (RR)-TB was only 59% worldwide [

2]. MDR-TB is a significant public health problem and a major global obstacle to the elimination of TB [

1].

Rapid diagnosis and an effective treatment regimen are essential for achieving treatment success in patients with MDR-TB 3 . However, in the absence of randomized controlled trials, the prioritization and combination of anti-TB drugs that are required to effectively treat MDR-TB have largely been based on meta-analyses of individual patient data, which in most cases originated from observational studies [

1,

4]. Although the level of evidence in a meta-analysis may not be sufficient, real-world evidence for the efficacies of core anti-TB drugs and their combinations prescribed based on these studies and treatment guidelines continues to accumulate.

Fluoroquinolones (FQs), such as levofloxacin (LFX) or moxifloxacin (MFX), are the most important core anti-TB drugs for treating MDR-TB, given their excellent bactericidal and sterilizing activities [

5]. If FQs are excluded from a treatment regimen due to resistance or intolerance, the treatment success rates for MDR-TB decrease considerably [

4,

6,

7]. Thus, developing an effective treatment regimen for fluoroquinolone-resistant (FQr)-MDR-TB is a difficult clinical problem, given the limited number of available core anti-TB drugs and high rates of resistance to anti-TB drugs other than FQs [

8]. The global estimate of the FQ resistance rate among all MDR-TB cases is approximately 20% [

9]. However, which anti-TB drugs are effective in patients with FQr-MDR-TB is unclear. Although the guidelines suggest several options for FQr-MDR-TB treatment (e.g., a longer individualized regimen or ŌĆ£bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid [BPaL] regimenŌĆØ), supporting evidence is still lacking [

1].

The aim of this study, based on nationwide data from South Korea, was to evaluate the impact of anti-TB drug use on treatment outcomes in patients with pulmonary FQr-MDR-TB. FQr-MDR-TB was defined as TB infection that is resistant to any FQ (ofloxacin [OFX], LFX, or MFX) in addition to MDR-TB.

Materials and Methods

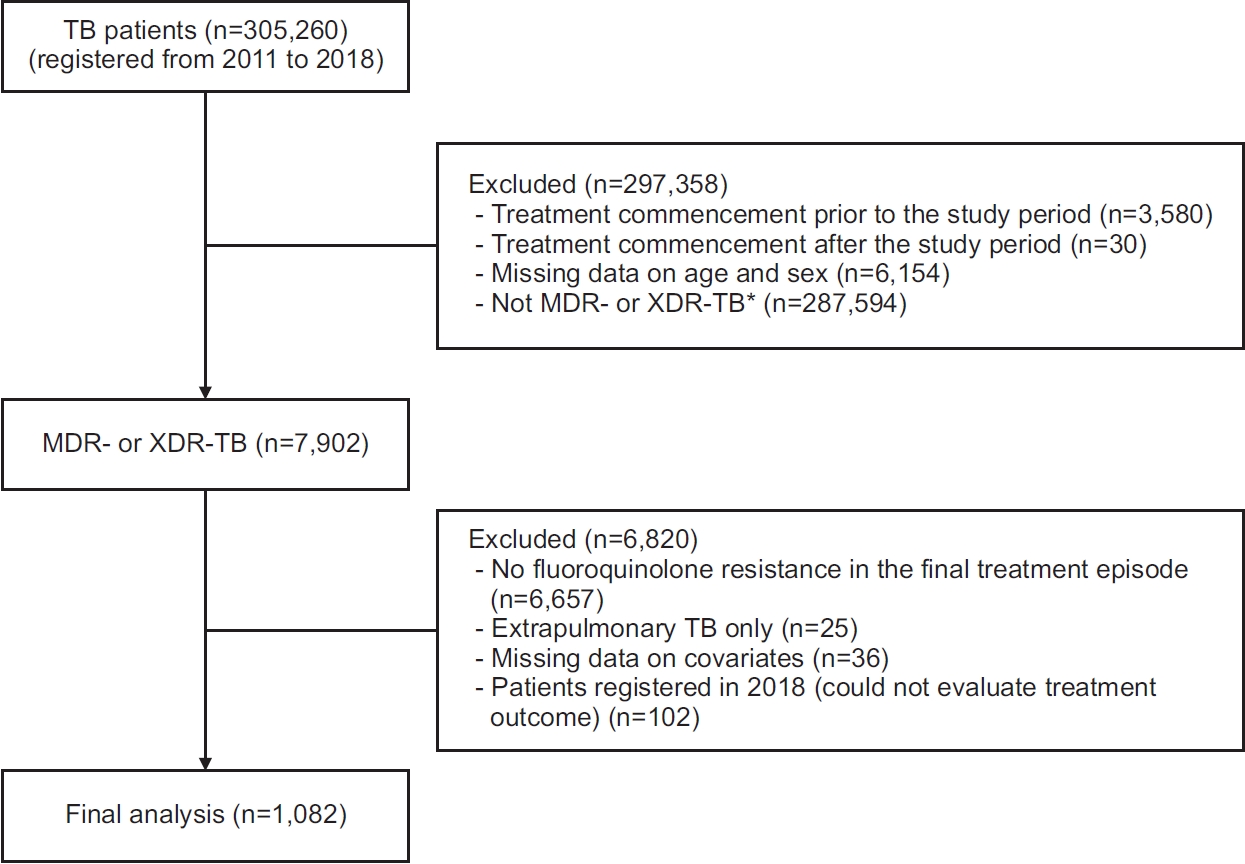

1. Study design and population

This retrospective study was performed in South Korea, where the TB notification rates of new cases were 78.9 and 55.0 per 100,000 population in 2011 and 2017, respectively [

10]. In 2017, 3.2% of new patients and 10.0% of previously treated patients had MDR-TB [

11]. The population for this study was extracted from the original TB cohort (Korean Tuberculosis and Post-Tuberculosis [Korean TB-POST]) generated by linkage of the Korean National Tuberculosis Surveillance System (KNTSS) with the National Health Information Database (NHID) and the Causes of Death Statistics Database [

12]. Among TB patients registered in the TB-POST cohort between 2011 and 2018, the following patients were included: patients with TB resistant to isoniazid (INH), rifampicin (RIF), and any FQ (OFX, LFX, or MFX) as demonstrated on a drug-susceptibility test (DST) from the KNTSS; and patients with extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-TB (as formerly defined by the World Health Organization [WHO] [

13]; patients with MDR-TB resistant to FQ and at least one of the three second-line injectable drugs [SLIDs] [kanamycin (KM), amikacin, and capreomycin]) according to the KNTSS record of drug resistance; and patients with the Korean Standard Classification Diseases code U84.31 (compatible with XDR-TB, as formerly defined by the WHO [

13]) from the NHID. If a patient notified the registries of additional treatment episodes after the end of the first treatment episode, data on the last treatment episode were collected in accordance with the inclusion criteria described above. Patients with extrapulmonary TB only or with missing data among any covariates were excluded from the analysis. Patients who were registered in 2018 were also excluded because of the unknown treatment outcome. The study population comprised the population registered in the KNTSS from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2017. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (NECAIRB19-008-1). The requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study using public de-identified data.

2. Measurement and definition

ŌĆ£Drug givenŌĆØ was defined as prescription of an anti-TB drug for at least 30 days during the treatment period. The following anti-TB drugs were evaluated: bedaquiline (BDQ), linezolid (LZD), OFX, LFX, MFX, cycloserine (CS), delamanid (DLM), ethambutol (EMB), pyrazinamide (PZA), streptomycin (SM), amikacin (AMK), KM, meropenem (MPM), prothionamide (PTO), and para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS). Drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis was defined when health institutions reported strain resistance to anti-TB drugs based on the DST results; otherwise, the strain was considered susceptible.

The history of TB treatment was defined as follows: New patients were those who had never been treated or who had taken anti-TB drugs for <1 month, and previously treated patients were those who had received anti-TB drugs for Ōēź1 month [

13]. Treatment outcomes at treatment completion were categorized in accordance with the WHO definitions as follows: cured, treatment completed, treatment failed, died (TB-related- and non-TB-related death), lost to follow-up, or not evaluated [

13]. Treatment success was defined as the sum of cured and treatment completed. For analyses of the effect of each anti-TB drug on the treatment outcome, an unfavorable outcome was defined as the sum of treatment failed, lost to follow-up, and not evaluated; death was defined as the sum of TB-related and non-TB-related deaths during treatment and within 12 months after treatment completion. The following covariates were included: age, sex, nationality, previous treatment history of TB, sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear result, comorbidity (diabetes mellitus [DM], malignancy, end-stage renal disease, and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection), number of resistant drugs, and resistance to a SLID.

3. DST and TB treatment

Phenotypic DST was performed using the absolute concentration method and Lowenstein-Jensen medium. The drugs and their critical concentrations for resistance were as follows: INH, 0.2 ╬╝g/mL; RIF, 40 ╬╝g/mL; EMB, 2.0 ╬╝g/mL; OFX, 2.0 ╬╝g/mL; LFX, 2.0 ╬╝g/mL; MFX, 2.0 ╬╝g/mL; SM, 10 ╬╝g/mL; AMK, 40 ╬╝g/mL; KM, 40 ╬╝g/mL; PTO, 40 ╬╝g/mL; CS, 30 ╬╝g/mL; PAS, 1.0 ╬╝g/mL; and LZD, 2.0 ╬╝g/mL. PZA susceptibility was determined using the pyrazinamidase test. The critical concentrations for resistance to AMK, KM, and OFX were changed during the study period as follows: AMK and KM, 30 ╬╝g/mL in January 2014; and OFX, 4.0 ╬╝g/mL in January 2016. Tests for LZD have been available since 2016. Molecular DSTs included line probe assays for first- or second-line anti-TB drugs and the Xpert MTB/RIF assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA); all tests were performed according to the manufacturersŌĆÖ instructions. To determine BDQ resistance, the minimum inhibitory concentration was determined using 7H9 broth and the serial two-fold dilution method. The concentration of BDQ was in the range of 0.03125 to 4.0 mg/L. The interim critical concentration for BDQ resistance was 0.25 mg/L. Tests for BDQ have been available since 2017. Isolates before 2016 and 2017 were considered susceptible to LZD and BDQ, respectively. It was assumed that all isolates were susceptible to DLM and MPM.

The treatment regimen for FQr-MDR-TB was individualized based on the DST result, and it was in line with the Korean guidelines. The regimens and treatment durations recommended by these guidelines are similar to the WHO guidelines: at least four effective second-line anti-TB drugs with or without PZA for at least 20 months [

14-

16]. In South Korea, BDQ and DLM have been available since March 2014 and October 2014, respectively. Indications for their use were in accordance with the WHO guidelines [

16].

4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables are presented as a number with a percent. The distribution by treatment outcomes was analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test or the Cochran-Armitage test for the test of trend. As our study was based on real-world data, propensity score matching (PSM) was used to balance the baseline characteristics of the ŌĆ£drug givenŌĆØ and ŌĆ£drug not givenŌĆØ groups. Drug use (given or not given) was considered as the dependent variable, and the following covariates were included in the PSM: age, sex, AFB smear result, previous treatment history of TB, resistance to SLIDs, number of resistant drugs, DM, and malignancy. The caliper method with a difference of 0.01 and 1:1 matching without replacement were used in the PSM. The impact of anti-TB drug use on the treatment outcome was determined in a multivariate logistic regression model. Treatment success was compared with unfavorable outcomes, and death with treatment success stratified by drug-resistance pattern and including covariates (age, sex, AFB smear result, history of TB treatment, resistance to SLIDs, number of resistant drugs, DM, and malignancy). Although all patients were included in the Pearson chi-square and Cochran-Armitage analyses conducted to assess the epidemiological trends in FQr-MDR-TB in South Korea, one patient with BDQ resistance was excluded from the final logistic regression analysis, as were 24 patients with LZD resistance, due to the small number of cases. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA/MP4 version 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). A p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Discussion

In this study, most drugs used against susceptible strains were associated with better outcomes in terms of increased treatment success and decreased mortality. This finding is in line with that of a meta-analysis of patients with RR/MDR-TB [

4], and it highlights the importance of DST-guided regimen selection for treating FQr-MDR-TB. Thus, DSTs should be expanded to include not only core anti-TB drugs but also the companion drugs used to treat FQr-MDR-TB. Compared with the treatment outcomes of patients with FQ-susceptible MDR-TB in previous South Korean studies, the treatment outcomes of patients with FQr-MDR-TB in our study were poorer [

17,

18]. This result demonstrates both the importance of FQs as core anti-TB drugs and the need for rapid detection of FQ resistance.

Not surprisingly, BDQ use and LZD use were associated with increased treatment success in patients with FQr-MDR-TB. However, these drugs did not affect mortality. Although this result may reflect the unique characteristics of FQr-MDR-TB patients or non-TB-related death after treatment completion, it was assumed that more severe disease in patients treated with BDQ and LZD would in turn increase the mortality. During the study period, BDQ use and LZD use in South Korea were authorized only for patients who could not be treated with conventional anti-TB drugs (e.g., due to high-level resistance). Also, the patients in our cohort who were treated with BDQ were older and had TB that was resistant to a larger number of drugs than patients who did not receive BDQ (

Supplementary Table S3). Even if we apply the PSM method to maintain balance between the groups that were given and not given a drug, unmeasured confounders may remain. For example, old age was an independent predictor of more deaths in the group that used BDQ, LZD, DLM, and MFX compared with the group that was not given these drugs (data not shown). However, DLM, another new anti-TB drug, was not associated with treatment success or death. Like BDQ, severe TB in patients treated with DLM might have affected the analysis. The clinical decision to use DLM for FQr-MDR-TB patients may be influenced by disease severity, as indicated by the total number of resistant drugs. For example, DLM was probably administered to patients with high resistance to other drugs (

Supplementary Table S3). Similar trends would likely be seen in patients treated with BDQ and LZD. Patients who were resistant to more than nine drugs were likely to be treated with BDQ, LZD, and DLM (

Supplementary Table S3). Although we tried to reduce confounding using several statistical methods, these factors may nevertheless have affected the analysis. In a previous study conducted in South Korea that included 131 patients with FQr-MDR-TB, there was no difference in the treatment success rates between the BDQ and DLM groups [

19]. The role of DLM in treating FQr-MDR-TB should be further investigated. First-line (e.g., EMB and PZA) and companion second-line (e.g., CS, PTO, and PAS) anti-TB drugs known to have weak or modest efficacies against RR/MDR-TB were beneficial in our study. This may be because these drugs are more efficacious under a ŌĆ£weakŌĆØ treatment regimen, i.e., in the absence of FQs, a group of strong core anti-TB drugs, as the latter were excluded.

Since the revision of the WHOŌĆÖs guidelines in 2018, SLIDs are no longer considered core anti-TB drugs for treating RR/MDR-TB [

20]. This recommendation was mainly based on the side effects, adherence rate, and limited efficacies of SLIDs. However, given their excellent bactericidal activities and their ability to prevent resistance, SLIDs may be beneficial in FQr-MDR-TB patients with limited treatment options. In a previous study, acquired BDQ resistance during treatment was less frequent in patients with FQr-MDR-TB when SLIDs were included in the regimen [

21]. In a recent meta-analysis of individual patient data on SLIDs, SM or AMK use was associated with higher rates of cure in patients with FQr-MDR-TB, whereas neither KM nor capreomycin had any meaningful impact [

22]. In our study, among SLIDs, only KM was associated with increased treatment success. Whether this result was due to the characteristics of the patients included in our cohort or due to other factors still remains to be determined. Interestingly, in our patients, the use of LFX against a susceptible strain was associated with increased treatment success and decreased mortality. We speculate that these results might be attributed to OFX-resistant and LFX/MFX-susceptible patients. Although there is controversy regarding the impact of using later-generation FQs in cases where there is a discrepancy in DST results between OFX and LFX/MFX and how it may affect the treatment outcomes [

23,

24], our results support the use of later-generation FQs against susceptible strains in patients with FQr-MDR-TB. However, in the absence of clear evidence on the efficacy of FQs for treating FQr-MDR-TB, FQs should be used with caution and should not be considered ŌĆ£effectiveŌĆØ in patients with FQr-MDR-TB. The use of MFX against resistant strains was also associated with a higher treatment success rate. Low-level MFX resistance and the use of high-dose MFX might have affected the results, but this could not be investigated in our cohort.

The efficacy of an anti-TB drug and DST results are the most important considerations in the choice of a treatment regimen. However, phenotypic DST for several companion drugs may not be reliable and reproducible [

1]. Therefore, clinical decision-making should be based on both the DST results and previous treatment history to ensure that effective treatment regimens are prescribed, as well as on factors, such as the severity and site of the disease, comorbidities, risk of adverse events, drug interactions, and patient preference [

1]. In our study, the proportion of patients treated successfully increased, while the rates of loss to follow-up and non-evaluation decreased over the study period. In addition to the introduction and widespread use of rapid diagnostic tests for drug-resistant TB, as well as new and repurposed anti-TB drugs, advances in the national TB program (e.g., the implementation of a public-private mix program) might be a factor responsible for the positive outcomes of FQr-MDR-TB patients [

7,

17,

18]. Nevertheless, the rate of patients lost to follow-up was still high and non-TB-related deaths showed an increasing trend. These results emphasize the importance of a comprehensive approach in patients with FQr-MDR-TB, as this population is more vulnerable than those with FQ-susceptible MDR-TB. In addition, while clinicians should monitor the therapy and disease course, patients should be supported by health education, socioeconomic support, emotional/psychosocial assistance, palliative care, and management of adverse drug reactions, all of which would improve treatment adherence [

25]. Although these elements are essential components of patient-centered care, they are ignored by many national TB programs.

This study had several limitations. First, it was conducted only in South Korea and almost all patients included were HIV negative. Thus, the results may not be generalizable globally. Second, clinical factors affecting the treatment outcomes of TB patients were not fully investigated. The presence of a cavity, disease extent, body mass index, and nutritional status are well-known factors affecting the outcomes. These factors and other residual confounding factors might have influenced the results. Third, patient adherence to anti-TB drugs could not be considered, which may have caused bias in determining an ŌĆ£effectiveŌĆØ anti-TB drug. Fourth, non-TB-related death or death after treatment completion might not be associated with the use of an anti-TB drug. However, we followed the definitions and analytical methods that are commonly used globally. Finally, the impact of clofazimine, another important anti-TB drug in the revised guidelines, was not evaluated because of the small number of patients treated accordingly.

In conclusion, DST-guided regimen selection is important in treating patients with pulmonary FQr-MDR-TB. In addition to core anti-TB drugs, such as BDQ and LZD, the use of later-generation FQs and KM against susceptible strains may be beneficial for patients with limited treatment options. Additional studies are warranted to obtain additional evidence on the efficacies of anti-TB drugs and regimens for treating FQr-MDR-TB, a hard-to-treat disease.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Data Sharing Statement

Data Sharing Statement Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Supplement1

Supplement1 Print

Print Download Citation

Download Citation