Tuberculosis Surveillance and Monitoring under the National Public-Private Mix Tuberculosis Control Project in South Korea 2016–2017

Article information

Abstract

Background

The national Public-Private Mix (PPM) tuberculosis (TB) control project provides for the comprehensive management of TB patients at private hospitals in South Korea. Surveillance and monitoring of TB under the PPM project are essential toward achieving TB elimination goals.

Methods

TB is a nationally notifiable disease in South Korea and is monitored using the surveillance system. The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quarterly generates monitoring indicators for TB management, used to evaluate activities of the PPM hospitals by the central steering committee of the national PPM TB control project. Based on the notification date, TB patients at PPM hospitals were enrolled in each quarter, forming a cohort, and followed up for at least 12 months to identify treatment outcomes. This report analyzed the dataset of cohorts the first quarter of 2016 through the fourth quarter of 2017.

Results

The coverage of sputum, smear, and culture tests among the pulmonary TB cases were 92.8% and 91.5%, respectively. The percentage of positive sputum smear and culture test results were 30.7% and 61.5%, respectively. The coverage of drug susceptibility tests among the culture-confirmed cases was 92.8%. The treatment success rate among the smear-positive drug-susceptible cases was 83.2%. The coverage of latent TB infection treatment among the childhood TB contacts was significantly higher than that among the adult contacts (85.6% vs. 56.0%, p=0.001).

Conclusion

This is the first official report to analyze monitoring indicators, describing the current status of the national PPM TB control project. To sustain its effect, strengthening the monitoring and evaluation systems is essential.

Introduction

In 1993, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared tuberculosis (TB) a global public health emergency and initiated the directly observed treatment short course (DOTS) strategy [1], which was primarily implemented through national TB programs (NTPs), with a focus largely on the public sector. Significant proportions of people with TB, however, do not necessarily seek care from public sectors, and private sectors do not often provide essential and high-quality TB care to patients who prefer to seek private providers [2]. Thus, a Public-Private Mix (PPM) approach was introduced in some developing countries during the late 1990s. Given the initial success of the approach, PPM approach became an essential component of the WHO’s Stop TB Strategy [3].

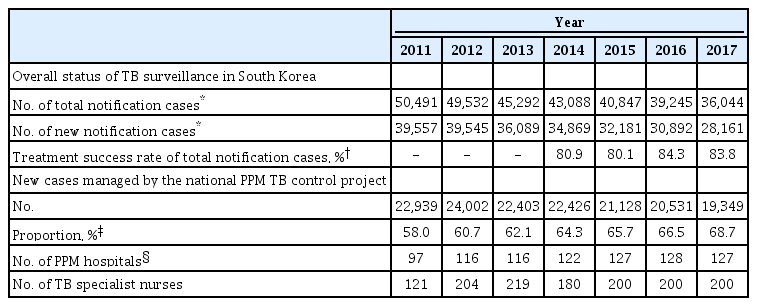

In 1989, South Korea achieved universal health coverage of its population [4]. With easier accessibility and improved quality of private health care, the proportion of TB patients notified at the private sectors increased substantially to 74.1% in 2006 [5]. However, treatment success rate at the private sectors was lower than that at the public sectors mainly owing to loss to follow-up [6,7]. To ensure better patient support for treatment adherence at the private sectors and thus improve treatment outcome, South Korea strengthened PPM cooperation. The national PPM TB control project was officially implemented in 2011 at 97 hospitals and expanded to 127 hospitals in 2017 [8], as shown in Table 1 [9,10].

Status of the tuberculosis patient management under the national PPM tuberculosis control project in South Korea 2011–2017

The main aim of implementing the PPM collaboration model in the Korean NTP is to improve case detection and management by including all patients under the surveillance system [11]. It is important to monitor the process of the PPM collaboration model in relation to defined objectives. Using the Korean National TB Surveillance System (KNTSS), the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) has quarterly generated monitoring indicators of TB management since 2014, which are used to evaluate activities of PPM hospitals by the central steering committee of the national PPM TB control project. This report provides an overview of its progress made and describes monitoring indicators of notified TB cases under the national PPM TB control project between 2016 and 2017.

Materials and Methods

1. National PPM TB control project

The national PPM TB control project was started in February 2009 at 22 private medical institutions with the aim of improving the treatment success rate of TB patients [5]. This project subsequently expanded nationwide in 2011. The national PPM TB control project is operated by the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases under the supervision of the KCDC. There are “Central Steering Committees” and “21 Regional Committees” to monitor the patient management of PPM hospitals. In 2017, 236 public health officials in 254 public health centers in municipalities and more than 210 nurses at 127 PPM hospitals were participating [8]. TB specialist nurses provide comprehensive patient management, which includes case studies, administration of anti-TB drugs during the infectious period, management of adverse drug reactions, and contact investigation among family members.

2. Data collection

TB is a nationally notifiable disease in South Korea and is monitored using the KNTSS, a web-based system launched in 2000 [8]. According to the Tuberculosis Prevention Act, notification to the public health center is mandatory when a physician diagnoses or treats a patient with confirmed or suspected TB or when a physician or another medical personnel performs a “postmortem” examination for a confirmed or suspectedTB case. The notification data include the patients’ personal information, examination results, treatments, and treatment outcomes. The previous study evaluated the completeness of the web-based notification, which revealed that completeness values increased from 90.0% in 2012 to 94.0% in 2014 [12].

3. Korean PPM monitoring database

The Korean PPM monitoring database includes data from patients notified at the PPM hospitals, which account for more than 60% of all TB cases reported nationwide, as shown in Table 1. Based on the notification date, TB patients at the PPM hospitals are enrolled in each quarter of the calendar year, which forms a cohort. The KCDC has the primary responsibility of accessing the TB notification data of the KNTSS, generating and updating indicators of each cohort every quarter, and releasing the data in the first month of next quarter. For example, data of patient cohort enrolled between the first day of January and the last day of March are registered and collected, and monitoring indicators are generated in April, as shown in Figure 1. The updated data of patient cohort are again collected between April and June. Every cohort is updated and analyzed five times in the same way, thus following up for at least 12 months to identify final treatment outcomes. This current report analyzed dataset of cohorts, which were registered between the first quarter of 2016 and fourth quarter of 2017. The monitoring indicators of a cohort registered in the fourth quarter of 2017 were finally updated and released in January 2019. The central steering committee of the national PPM control project receives the monitoring indicators and evaluates activities of the PPM hospitals.

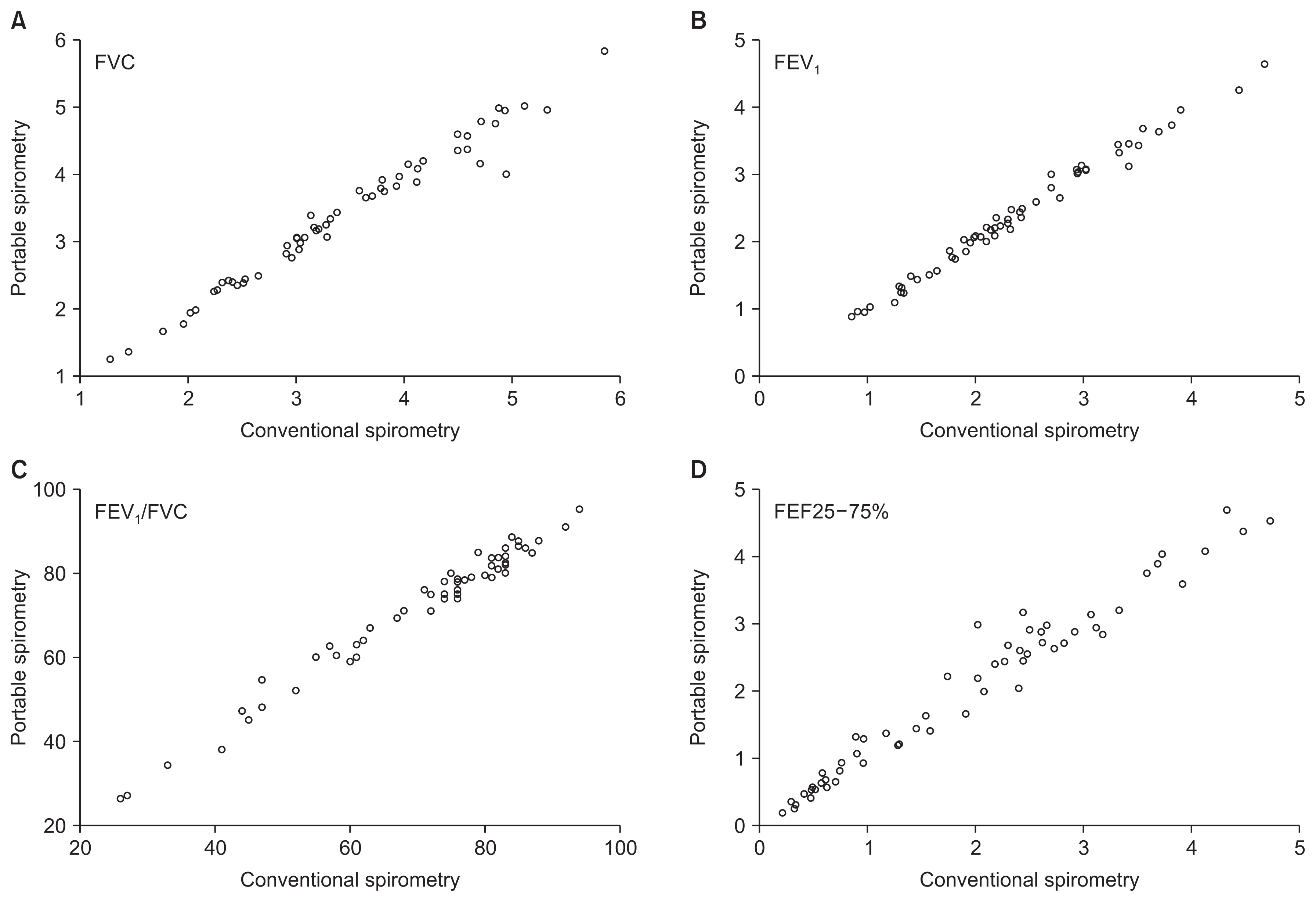

4. Definitions of core indicators and treatment outcome

Of the 25 monitoring indicators, eight for active TB cases and four for contact investigations and latent TB infection (LTBI) cases were collected in this report, as shown in Table 2. All the indicators are expressed in proportion. After exclusion of cases with a final diagnosis other than TB, all TB cases notified in each quarter of interest were followed for at least 12 months, and their final outcomes were reported in accordance with the WHO treatment outcome definitions [13], which was endorsed by the Korean TB guidelines [14]. The additional category, “still on treatment,” is defined as patient still on treatment at the fifth analysis of each cohort without any other outcome during treatment. Treatment success is the sum of “cured” and “treatment completed.” To report the treatment success rate among smear-positive drug-susceptible pulmonary TB cohorts, we included cases with resistance to isoniazid, ethambutol, and/or pyrazinamide but without resistance to rifampicin in the drug-susceptible cohorts. Therefore, this cohort represented patients who are indicated for standard anti-TB treatment regimen and expected to finish their anti-TB treatment within 12 months.

5. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as numbers (with percentages). Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson chi-square test. To evaluate quarterly trends of each monitoring indicator, the chi-square test for trend was performed. All tests were two-tailed, and p<0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

6. Ethical statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea approved the study protocol (DC20ZASI003) and waived the need for informed consent because no patients were at risk.

Results

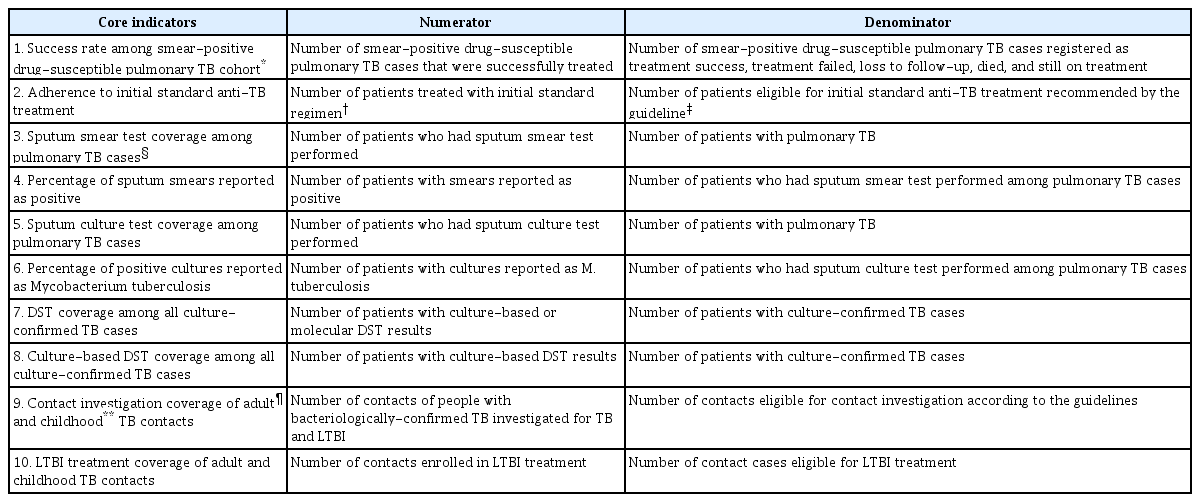

Of 26,216 pulmonary TB cases notified in 2016, 92.2% (24,164) and 90.9% (23,823) had sputum smear and culture tests performed, respectively, as shown in Table 3. Of 24,893 pulmonary TB cases notified in 2017, 93.4% (23,251) and 92.2% (22,961) had sputum smear and culture tests performed, respectively. Sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear and culture test coverages between the first quarter of 2016 and the fourth quarter of 2017 were significantly increased from 91.0% to 94.1% (p<0.001) and from 90.4% to 93.6% (p<0.001), respectively, as shown in Figure 2A. Percentages of positive results of sputum smear tests in 2016 and 2017 were 31.8% (7,675/24,164) and 29.6% (6,876/23,251), respectively. Percentages of positive results of sputum culture tests in 2016 and 2017 were 62.9% (14,985/23,823) and 60.1% (13,804/22,961), respectively.

Sputum AFB smear and culture test coverage and percentage of their positive results among the pulmonary TB cases 2016–2017

Trend in the microbiological test coverage 2016–2017. (A) Sputum acid-fast bacillus smear and culture test coverage among the pulmonary tuberculosis cases. (B) Drug susceptibility test coverage among the culture-confirmed tuberculosis cases.

Coverages of culture-based or molecular drug susceptibility tests (DST) among all notified TB cases confirmed by culture in 2016 and 2017 were 92.5% (14,953/16,165) and 93.2% (13,881/14,901), respectively. DST coverage was significantly increased from 91.3% in the first quarter of 2016 to 93.1% in the fourth quarter of 2017 (p=0.005), as shown in Figure 2B. Coverage of conventional culture-based DST was above 90% in both 2016 and 2017.

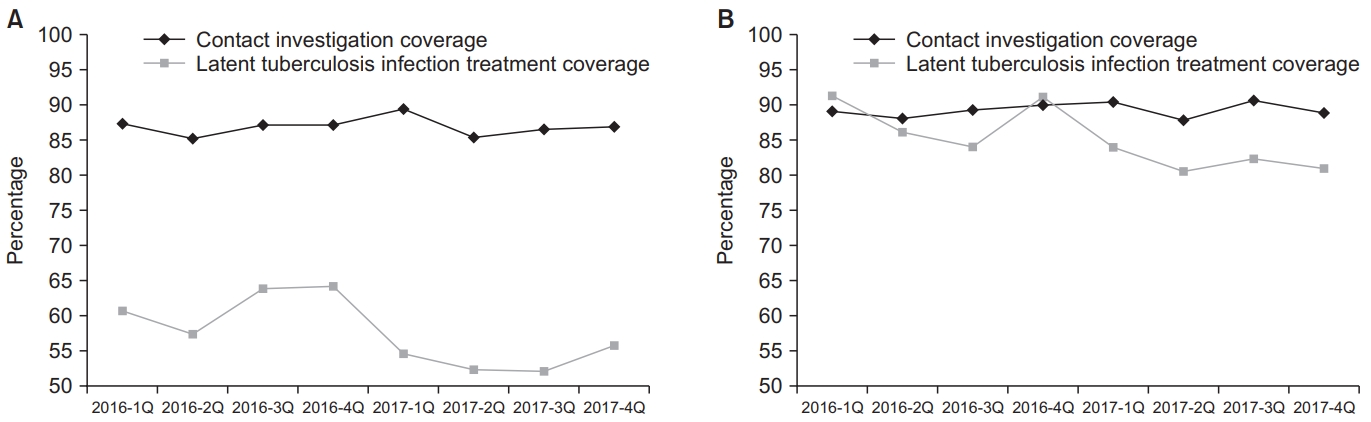

Adherence rates to initial standard anti-TB treatment recommended by the guideline were 93.7% in both 2016 and 2017, as shown in Table 4. All the administrative regions had adherence rates above 90%, with the highest rate in the Ulsan Metropolitan City (96.9% in 2016 and 96.7% in 2017). Gangwon-do had the lowest adherence rate of 91.5% in 2016, and Daegu had the lowest rate of 91.0% in 2017. Adherence rates between the first quarter of 2016 and the fourth quarter of 2017 decreased from 94.1% to 93.2% but was not statistically significant (p=0.134), as shown in Figure 3.

Adherence rate to initial standard anti-TB treatment recommended by the guidelines by administrative regions 2016–2017

Trend in the adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment recommended by the guideline and treatment success rate among the smear-positive drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis cohorts 2016–2017.

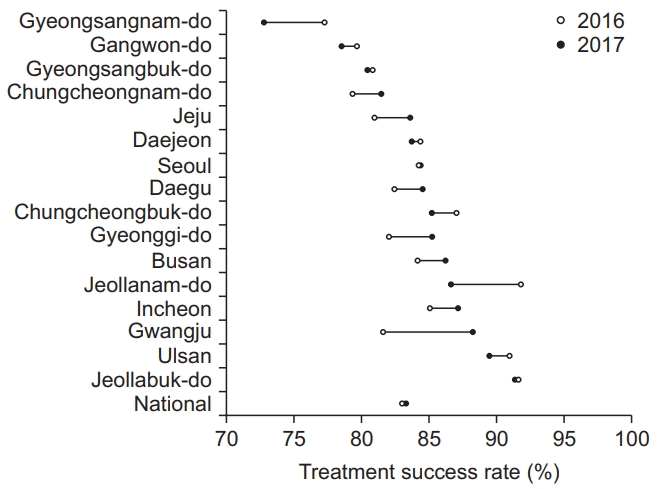

Treatment success rates among smear-positive drugsusceptible pulmonary TB cohort were 83.1% in 2016 and 83.4% in 2017, as shown in the Supplementary Table 1. The treatment success rate between the first quarter of 2016 and the fourth quarter of 2017 increased from 83.0% to 84.6% but was not statistically significant (p=0.223), as shown in Figure 3. The treatment success rate varied by the administrative regions, with the highest rate in Jeollanam-do (91.9% in 2016) and Jeollabuk-do (91.4% in 2017) and the lowest rate in Gyeongsangnam-do (77.4% in 2016 and 73.0% in 2017). In eight administrative regions, their treatment success rates in 2017 were numerically lower than those in 2016, as shown in Figure 4. Overall rates of treatment failure and loss to follow-up among smear-positive drug-susceptible pulmonary TB in 2016–2017 were 2.4% and 0.03%, respectively.

Trend in the treatment success rate among the smearpositive drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis cohort by the administrative regions 2016–2017.

Contact investigation coverages of adult TB contacts in 2016 and 2017 varied between 85.2% and 89.4% (p=0.983), as shown in Figure 5. Contact investigation coverage of childhood TB contacts also varied between 87.7% and 90.5% (p=0.473). Coverage of LTBI treatment among childhood TB contacts was significantly higher than that among adult con-tacts (85.6% vs. 56.0%, p<0.001). LTBI treatment coverages of both adult and childhood TB contacts from the first quarter of 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2017 significantly decreased from 60.8% to 55.7% (p<0.001) and from 91.3% to 81.0% (p<0.001), respectively.

Discussion

This is the first official report assessing the implementation of TB patient management under the national PPM TB control project in South Korea. After its nationwide expansion in 2011, the proportion of new TB cases managed under the PPM project has increased from 58.0% in 2011 to 68.7% in 2017, as shown in Supplementary Table 1. Patient treatment and management based on the PPM project have made a significant contribution to the overall treatment success rate for TB patients in South Korea, which has improved from 80.9% in 2014 to 83.8% in 2017 [15]. Based on the notification data from the KNTSS, the rate of total notified TB cases has decreased from 100.8 per 100,000 in 2011 to 76.8 per 100,000 in 2016. The government of Korea established the second National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Control (2018–2022) with the goal of lowering the incidence rate of TB to 40 per 100,000 by 2022. One of top priorities for TB control is systematic and comprehensive management of TB patients under the national PPM TB control project along with its reinforcement. Strong monitoring and evaluation systems are essential to report accurate, timely, and comparable data that can be used to inform decision-making and to demonstrate progress [16]. The central steering committee of the PPM project performs monitoring and evaluation periodically and disseminates their result to all the stakeholders to guide activities effectively through identifying challenges, barriers, and opportunities for program improvement.

Before interpreting the monitoring indicators described in the result section, it is important to note that these indicators were developed to assess the performance of the individual PPM hospitals. Thus, current data in this report does not represent the overall status of TB control in South Korea and are different from those in the annual TB report published by the KCDC. Because different definitions of denominators were employed to calculate each indicator, readers should understand definitions of monitoring indicators before comparing them with data in the other resources.

In 2016 and 2017, coverage of sputum AFB smear and culture tests among the notified pulmonary TB cases, which are the main indicators for TB management in the PPM project, were over 90%. Since bacteriological testing remains the mainstay of TB diagnosis, access to quality assured sputum microscopy for case detection is a key component of the expanded DOTS strategy [17]. The Korean TB guidelines recommends performing both AFB smear and culture tests simultaneously for mycobacterial examination [14]. Coverage of DST (conventional culture-based or rapid molecular) among the notified culture-confirmed TB cases was also above 90%. Although rapid molecular DSTs were not frequently performed in South Korea until recently [18], their usefulness continues to be emphasized by guidelines in the light of the importance of rapid diagnosis of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). Assessment of rapid molecular DST coverage even in new TB cases would help understand the current status of drug-resistant TB management, since prevalence of both isoniazid and rifampicin resistance is relatively high in South Korea. In 2016 and 2017, average positive results of AFB smear and culture tests were 30.7% and 61.5%, respectively, in South Korea, given that both test coverages were over 90%. It is important to determine the baseline of positivity of smear and culture tests and observe its trend along with time [19]. As fluctuation or deviation of these indicators are noticed, appropriate investigations should be introduced to assess TB epidemics, laboratory cross-contamination, or poor laboratory performance.

In all the administrative regions, adherence rate to initial standard anti-TB treatment by the Korean TB guideline was higher than 90%. Because current TB surveillance system does not distinguish patients who have been transferred between two treatment units, patients using second-line anti-TB drugs because of side effects at the time of transfer were included in the denominator of the adherence rate, which presumably lowered this indicator especially in those administrative regions where many tertiary PPM hospitals are located. We identified regional variation of treatment success rate among smear-positive drug-susceptible pulmonary TB cohort from 73% to 91%. Understanding the different characteristics of TB patients at each administrative region would help identify the cause of this large difference. For example, high TB incidence in the elderly population is an important issue in South Korea [20], which contributes to high mortality rate and low treatment success rate. There is a need for public health interventions tailored to the characteristics of each region, which requires collaboration of local government and PPM hospitals.

For treatment outcome analysis among drug-susceptible pulmonary TB cohort, we excluded cases with rifampicinresistance, including rifampicin-monoresistant TB and MDR-TB. The number of notifiable MDR-TB cases has decreased recently in South Korea [21]; however, a recent study showed that management of MDR-TB patients under the national PPM TB control project is insufficient [22]. MDR-TB is a great public health threat in South Korea and has drawn attention to the crucial need for better support and management. Introduction of indicators assessing treatment outcome for MDR-TB is necessary to understand its status and plan any public health interventions or policies.

It is noteworthy that patients who “transferred out” to another treatment unit, returned to their home country, and died of non-TB–related causes were not included in the denominators of treatment outcome and were excluded from analysis. Thus, treatment success rate in this report might lose important individual data and be overestimated. For example, those who transferred out might not visit another treatment unit, which should be classified as “loss to follow-up.” Those patients with TB-related death might be falsely classified as “non-TB–related causes” because it is challenging to identify the correct mode of death, especially for elderly individuals, in routine clinical practice [23].

South Korea has established policies to strengthen the management of LTBI along with the WHO guideline [24]. However, contact investigation and LTBI treatment have not yet been the major interests of the national PPM TB control project, which contributed to low LTBI treatment coverage especially for the adult TB contacts. The trend of LTBI treatment coverages in both adult and childhood TB contacts was decreasing between 2016 and 2017. One of the challenges in the LTBI management are a low perception of LTBI and difficulties to inform the public and healthcare professionals about the importance of its screening and treatment [25]. In 2017, a nationwide education program on LTBI was implemented for healthcare workers to overcome this challenge [8]. Financial support and political wills should be highlighted to achieve better LTBI management and increase LTBI treatment coverage.

To meet the WHO End TB target, the national PPM TB control project should consider expanding its programs to several areas of low interest, such as intensive family contact investigation, LTBI treatment, MDR-TB, and patients with low compliance. This should be supported holistically by well-trained and more-experienced TB specialist nurses as well as financially by the central government [8]. The role of the local government in NTP needs to be addressed [26,27]. For example, the local government should pay attention to the TB patients inadequately managed outside the PPM project and proactively act with the PPM hospitals to improve their management. Collaborations of multiple stakeholders at local, district, and national levels are essential under the national PPM TB control project.

In conclusion, this is the first official report to analyze monitoring indicators, which described the current status of the national PPM TB control project, despite its limited availability of accessible indicators. Our study identified a large regional variation of treatment success rate among smear-positive drug-susceptible pulmonary TB cohorts, and in-depth understanding of each region would help identify its cause. Nationwide education program on LTBI for healthcare workers along with financial support are essential to improve LTBI treatment coverage. Based on successful implementation of the PPM project along with its strengthened TB policy, South Korea has shown a 5.2% annual reduction in the incidence of new TB cases from 2011 to 2016 [8]. To sustain its effect, reinforcement of the PPM project is necessary through periodic monitoring and evaluation, which will provide knowledge and evidence for effective interventions to optimize TB policies and enhance service quality [16].

Notes

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: Kim JS, Lee SS, Park JS, Kang JY. Methodology: Kim JS, Min J, Kim HW, Ko Y. Formal analysis: Kim JS, Min J, Lee J, Oh JY. Data curation: Kim JS, Lee J. Writing - original draft preparation: Min J, Kim JS, Kim HW, Ko Y, Oh JY. Writing - review and editing: Min J, Lee SS, Park JS, Kang JY, Lee J. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The national PPM TB control project is supported by the National Health Promotion Fund, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Acknowledgements

The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, South Korea, has authority to hold and analyze surveillance data for public health and research purpose.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found in the journal homepage (http://www.e-trd.org).

Supplementary Table S1. Treatment success rate among smear-positive drug-susceptible pulmonary TB cohort by administrative regions in 2016 and 2017.