Non-Surgical Management of Critically Compromised Airway Due to Dilatation of Interposed Colon

Article information

Abstract

We present a rare case of critically compromised airway secondary to a massively dilated sequestered colon conduit after several revision surgeries. A 71-year-old male patient had several operations after the diagnosis of gastric cancer. After initial treatment of pneumonia in the pulmonology department, he was transferred to the surgery department for feeding jejunostomy because of recurrent aspiration. However, he had respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed pneumonic consolidation at both lower lungs and massive dilatation of the substernal interposed colon compressing the trachea. The dilated interposed colon was originated from the right colon, which was sequestered after the recent esophageal reconstruction with left colon interposition resulting blind pouch at both ends. It was treated with CT-guided pigtail catheter drainage via right supraclavicular route, which was left in place for 2 weeks, and then removed. The patient remained well clinically, and was discharged home.

Introduction

For esophageal reconstruction, colon is considered as a well functioning and durable esophageal substitute1. There are several late complications after colon interposition for esophageal reconstruction; graft redundancy, anastomotic stricture, and adhesional obstruction23. Late complications after colonic interposition for esophageal reconstruction may lead to debilitating symptoms, poor quality of life, and malnutrition. We present a rare case of critically compromised airway secondary to a massively dilated sequestered colon conduit after several revision surgeries.

Case Report

A 71-year-old male patient had several operations after the diagnosis of gastric cancer. The first operation was laparoscopy assisted total gastrectomy with R-Y esophagojejunostomy 6 years ago. Because of anastomosis leakage after initial operation, he received esophagostomy and feeding jejunostomy, followed by esophageal reconstruction with right colon interposition. He consecutively had colon infarction requiring esophagostomy and feeding ileostomy. Four years later he received esophageal reconstruction with left colon interposition, followed by cervical esophagocolojejunostomy, which made his oral feeding possible. He is an ex-smoker, and had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring regular use of anticholinergic inhaler.

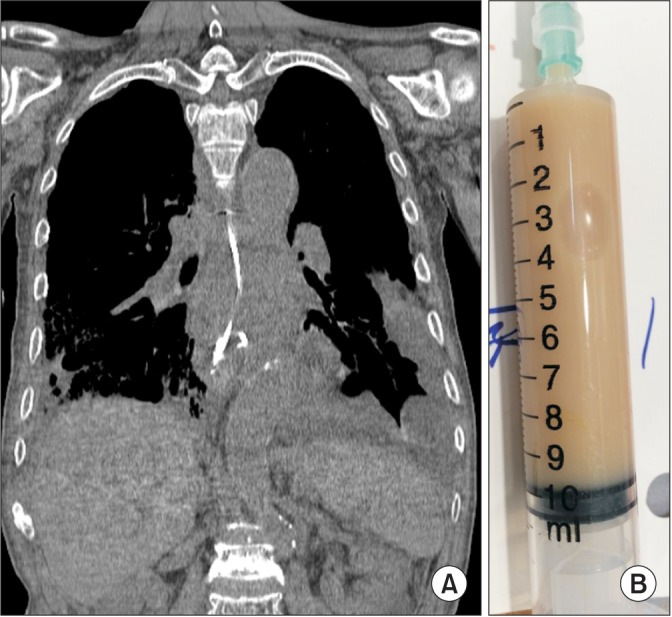

He initially presented with purulent sputum for several days, and admitted to medical ward for 2-week antibiotic treatment against community-acquired pneumonia. The initial chest computed tomography (CT) scan after the admission showed pneumonic consolidation at right lower lung. Although it also revealed the dilatation of interposed colon compressing the trachea and heart, the patient did not complain any symptoms associated with compression. After completing treatment, he was transferred to the surgery department for feeding jejunostomy because of recurrent episodes of aspiration during hospital stay. However, he restarted to have purulent sputum and eventually had respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU). The chest CT scan after admission to the ICU (Figure 1) showed pneumonic consolidation at both lower lungs and massive dilatation of the substernal interposed colon compressing the trachea. We believed that continuing silent aspiration of secretion caused aspiration pneumonia, and compromised airway hindered expectoration of sputum leading to respiratory failure. Antibiotic treatment against hospital-acquired pneumonia was started.

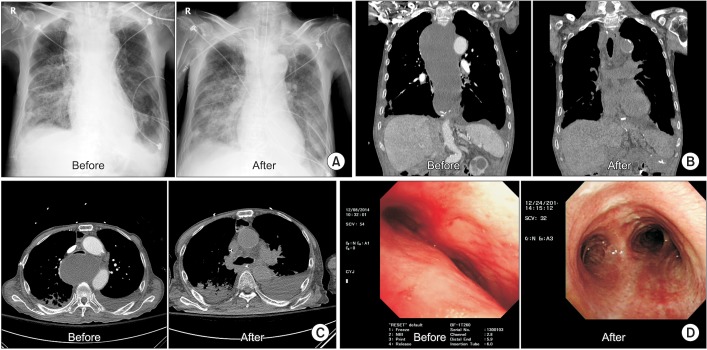

Chest X-ray, chest computed tomography (CT), and fiberoptic bronchoscopy before and after CT-guided pigtail catheter insertion. (A) Mediastinal widening was improved. (B) Sequestered interposed colon was shrunk. (C) Resolution of compressed trachea. (D) Extrinsic compression was resolved.

Although percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy was performed for long-term airway maintenance, he again suffered from respiratory distress and was re-intubated. A series of the chest CT scans was reviewed among intensivists, pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, and radiologists in order to manage the dilatation of the interposed colon compressing the trachea. The dilated interposed colon was originated from the right colon, which was sequestered after the recent esophageal reconstruction with left colon interposition resulting blind pouch at both ends. It has been increasing its size slowly but progressively. The dilatation of the interposed colon was treated with CT-guided pigtail catheter drainage via right supraclavicular route (Figure 2). It was left in place for 2 weeks, and then removed once the output was diminished to less than 10 mL per day. The patient remained well clinically, and was discharge home.

Discussion

It is a unique case of late complications after esophageal reconstruction. The previous interposed colon was not removed during the revision surgery, which was sequestered. Although it initially did not do any harm, its size was increased slowly resulting compression symptoms after several years. Nonsurgical management was chosen for this case because of his medical status after multi-disciplinary discussion.

Indications of esophageal reconstruction are esophageal cancer, non-malignant stenosis, esophageal fistula, megaesophagus, and necrosis of a previous esophageal substitute4. Colonic interposition is an established treatment for congenital esophageal atresia in children, and use of colon in the spectrum of esophageal cancer operation is widely used in adults. Among several late complications after colon interposition for esophageal reconstruction, conduit redundancy and dilatation are one of the well recognized complications. Common symptoms of the dilatation of the interposed colon include dysphagia, regurgitation, and aspiration; however, more serious complications compressing airway and heart may result respiratory distress and cardiac failure in a review of literature. There were two cases of expanding esophageal mucocele after esophageal exclusion and colonic interposition; the first case compressing airway5, and the second case compressing right recurrent laryngeal nerve6. Another case had massively dilated substernal colon conduit, which resulted extrapericardial compression7. Although these cases, including the current case, had the different mechanisms of the dilated mass, they have eventually resulted life-threatening mass effect on nearby structures.

Although some patients with late complications may be managed by nonsurgical methods, surgical revision is required in as many as one-fifth of the cases8. Colonic redundancy is the most common complication that requires surgery910. Definite management of a dilated mass in this case requires removal of the sequestered interposed colon, or at least eradication of residual mucosa. However, minimally invasive approach was pursued for this case because of malnutrition and chronic pulmonary disease. The percutaneous drainage under CT guidance for decompression was successfully done without any complications.

This case illustrates a rare but life-threatening compromised airway secondary to massive dilatation of the sequestered interposed colon after esophageal reconstruction. Earlier recognition of symptoms associated with compressing the nearby structures is important, and non-surgical management might be considered based on patient's general condition. In an era of medical intensivists taking care of both surgical and medical ICUs, a thorough understanding of postoperative complications is essential, and multidisciplinary approach should be sought.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.