Clinical Characteristics of Chronic Cough in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

Chronic cough is defined as a cough lasting more than 8 weeks and socio-economic burden of chronic cough is enormous. The characteristics of chronic cough in Korea are not well understood. The Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases (KATRD) published guidelines on cough management in 2014. The current study evaluated the clinical characteristics of chronic cough in Korea and the efficacy of the KATRD guidelines.

Methods

This was a multi-center, retrospective observational study conducted in Korea. The participants were over 18 years of age. They had coughs lasting more than 8 weeks. Subjects with current pulmonary diseases, smokers, ex-smokers with more than 10 pack-years or who quit within the past 1 year, pregnant women, and users of cough-inducing medications were excluded. Evaluation and management of cough followed the KATRD cough-management guidelines.

Results

Participants with chronic cough in Korea showed age in the late forties and cough duration of more than 1 year. Upper airway cough syndrome was the most common cause of cough, followed by cough-variant asthma (CVA). Gastro-esophageal reflux diseases and eosinophilic bronchitis were less frequently observed. Following the KATRD cough-management guidelines, 91.2% of the subjects improved after 4 weeks of treatment. Responders were younger, had a longer duration of cough, and an initial impression of CVA. In univariate and multivariate analyses, an initial impression of CVA was the only factor related to better treatment response.

Conclusion

The causes of chronic cough in Korea differed from those reported in other countries. The current Korean guidelines proved efficient for treating Korean patients with chronic cough.

Introduction

Cough is a basic airway defense mechanism and the most frequent cause of hospital visits1. The economic burden of cough is enormous. The United States spends over 9 billion dollars annually on cough and the United Kingdom over 0.9 billion pounds annually2. Chronic cough is defined as a cough lasting more than 8 weeks. The estimated overall adult prevalence is approximately 10% worldwide but varies by region3. The United States (11.0%) and Europe (12.7%) have higher prevalences than those of Asia (4.4%) and Africa (2.3%). There are no current data for Korea, although a survey reported the prevalence of chronic cough in the elderly to be 4.6%–9.3%4.

Chronic cough has various etiologies. The major causes are gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), asthma, and upper respiratory diseases (e.g., rhinitis, sinusitis, and post-nasal drip)56. Chronic respiratory diseases (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], bronchiectasis, lung cancer, and interstitial lung disease) and environmental factors (e.g., exposure to smoke, dust, and air pollution) also play roles7. Recently, cough hypersensitivity, laryngeal dysfunction, and idiopathic cough have been identified as refractory causes of chronic cough89. Because of its various etiologies, chronic cough is easily misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated. Only approximately half of patients improve following treatment in general clinics, whereas nine out of 10 improve after being treated by cough specialists following various guidelines101112. Many different guidelines have been developed7. The Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases (KATRD) developed cough-management guidelines in 2014, which reflected up-to-date guidelines and research data6. In this study, we evaluated both the causes and the clinical characteristics of chronic cough in Korea and the efficacy of these KATRD cough-management guidelines.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design

This was a multi-center, retrospective observational study. Patients who treated chronic cough from March 1, 2016, to February 28, 2018 were included. A total of 19 university hospitals participated nationwide.

The institutional review board of all hospital approved the study protocol, as did the Institutional Review Board of Catholic Medical Center (No. 2019-0810). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective observational nature of the study.

2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with a cough lasting more than 8 weeks and who were over 18 years of age were included. Those with abnormal findings on chest X-ray or with a chronic respiratory disease, such as asthma, COPD, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis-destroyed lung, or lung cancer, were excluded. Current smokers, ex-smokers with more than 10 pack-years, and ex-smokers who quit smoking within the past 1 year were also excluded. Patients taking cough-inducing medications (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) and pregnant women were also excluded.

3. Protocol for management of chronic cough

All researchers used the same chronic cough management protocol since 2014. All participants were managed and evaluated according to the 2014 KATRD cough-management guidelines6. Evaluation tests were performed simultaneously or stepwise. The initial impression of chronic-cough etiology was based on the symptoms or positive evaluation tests. Abnormal paranasal sinus (PNS) X-ray was defined by haziness, such as complete opacity, air-fluid level, loss of translucency of most of the maxillary sinus, and mucosal thickening. If the participant had an abnormal PNS X-ray, post-nasal drip, or rhinitis, upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) was suspected. If UACS was suspected, an antihistamine was given alone or in combination with a nasal decongestant1314. Cough-variant asthma (CVA) was suspected when sole symptom of cough without dyspnea or wheezing was noted and when bronchial hyper-responsiveness was found based on the bronchodilator response (BDR) or provocation test. Eosinophilic bronchitis (EB) was suspected based on the symptoms or sputum eosinophil count15. If the initial impression was CVA, an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) was given alone or together with a long-acting β-agonist (LABA). Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) and oral corticosteroids (OCSs) can be used as addon medications. If EB was suspected, ICS was given. LABA or OCS can also be given, although LTRA is not recommended. GERD was suspected if the patient had acid regurgitation and heartburn symptoms16 and was treated with a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI).

The abovementioned initial impressions of the chroniccough etiology were evaluated in order. First, UACS was evaluated, followed by CVA and EB and finally GERD. Treatment of the initial impression was maintained for 4 weeks if the cough improved. In the case of no response to the initial treatment, the second most likely cause was treated for up to 4 weeks, while the initial treatment was maintained. A final diagnosis of chronic cough was made if the cough improved. If none of UACS, CVA, EB, and GERD was suspected, additional evaluations were performed including chest computed tomography, echocardiography, allergy skin tests, immunoglobulin E measurement, and bronchoscopy. Other causes of refractory cough, such as psychogenic cough, idiopathic cough, and cough hypersensitivity, were considered after excluding other suspected diseases after additional evaluations.

4. Treatment response evaluation

A cough numeric rating scale (NRS) is widely used as a subjective assessment of cough because it is simple and easy to perform17. In this study, we evaluated cough status using a cough NRS consisting of a 10-cm line with marks positioned 1 cm apart. The leftmost mark was labeled “0” and represented “no cough.” The rightmost mark was labeled “10” and indicated “worst cough ever.” The treatment response was evaluated twice: first, after 1 week of treatment for UACS, CVA, and EB or 2 weeks for GERD and, second, after 4 weeks of treatment. Improvement was defined as a decrease in the cough NRS score of more than 50% or more than four points.

5. Statistical analysis

We performed subgroup analyses using the independent-samples t-test for continuous variables and Pearson's chisquare test for categorical variables. To evaluate the factors associated with treatment response, we performed binominal logistic regression analysis. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data are expressed as means±standard error of the mean or as numbers (%), and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

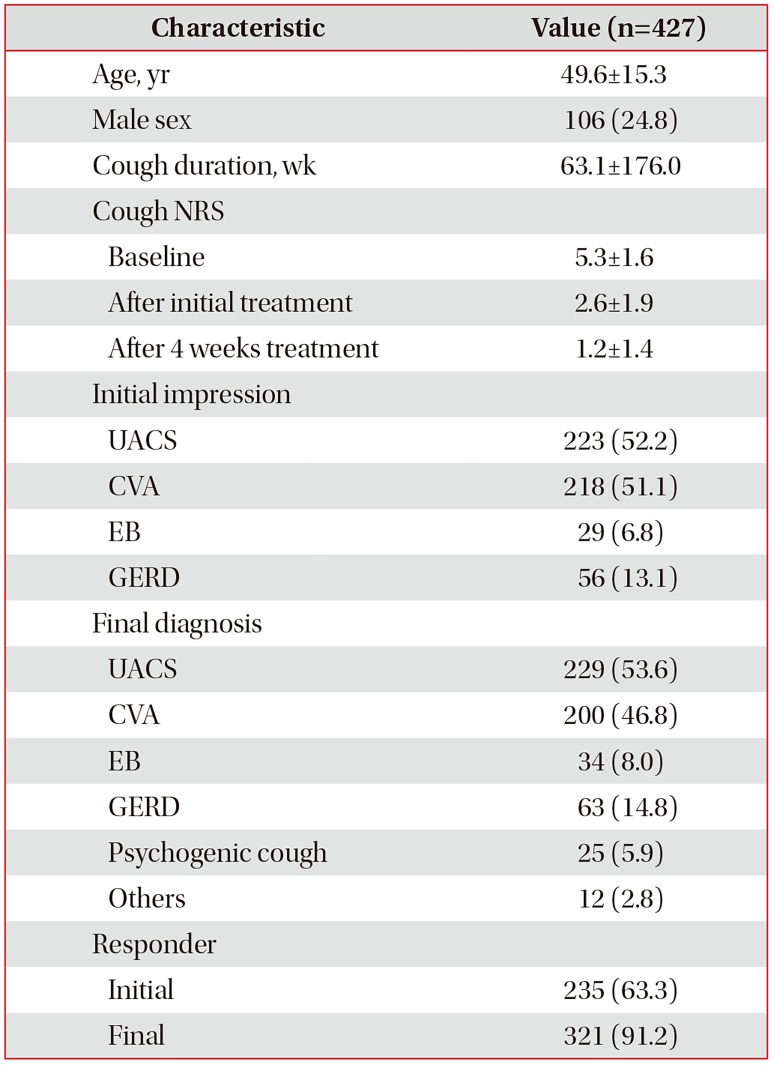

1. Baseline clinical characteristics

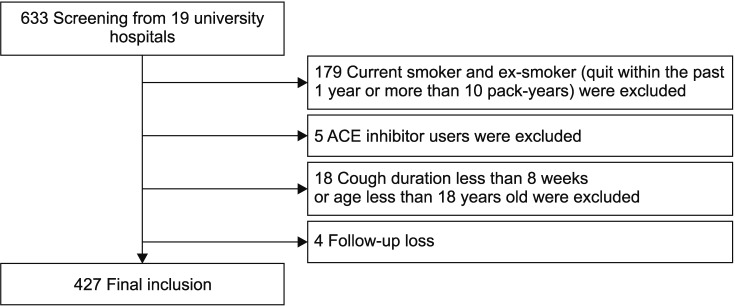

Ultimately, we analyzed 427 participants (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes their baseline characteristics. The mean duration of cough was 63.1±176.0 weeks. The cough NRS scores at baseline, after the initial treatment, and after 4 weeks of treatment were 5.3±1.6, 2.6±1.9, and 1.2±1.4, respectively. Among the initial impressions for cough etiology, UACS (52.2%) and CVA (51.1%) were suspected most often, followed by GERD (13.1%) and EB (6.8%). In the final diagnosis, UACS (53.6%) was the most common cause, followed by CVA (46.8%), GERD (14.8%), and EB (8.0%). Psychogenic cough (5.9%) and other causes (2.8%) were rare. Approximately 27.4% of the patients had two or more causes of chronic cough. Following the 2014 KATRD cough-management guidelines, 63.3% of the subjects improved after the initial treatment and 91.2% after 4 weeks of treatment. The female participants had an older mean age and higher prevalence of CVA compared with the male participants, whereas the other factors were not significantly different between the sexes (Table 2).

Flow diagram of study. Overall 633 patients were screened. Current smoker and ex-smoker (quit within the past 1 year or more than 10 pack-years) were excluded. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor users were excluded. Participants who were not more than 8 weeks of cough or 18 years old were excluded also. Four patients were lost during follow up. Finally, 427 participants were included in this study.

2. Characteristics of treatment responders and non-responders

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the responders and non-responders to chronic-cough treatments among the participants. The responders were younger (48.9±15.0 years vs. 51.5±17.8 years, p<0.001) and had a longer cough duration (65.6±164.1 weeks vs. 31.4±37.2 weeks, p=0.003) compared with the non-responders. An initial impression of CVA was more common among the responders (57.9% vs. 35.5%, p=0.016). Other factors such as sex, baseline cough NRS score, initial impression other than CVA, and final diagnosis did not differ significantly between the treatment responders and non-responders.

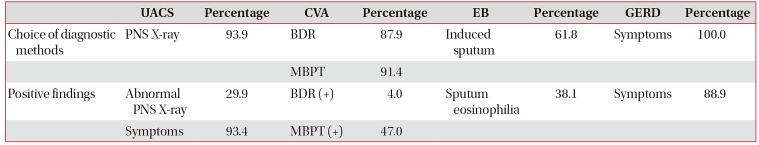

3. Subgroup analysis by diagnosis

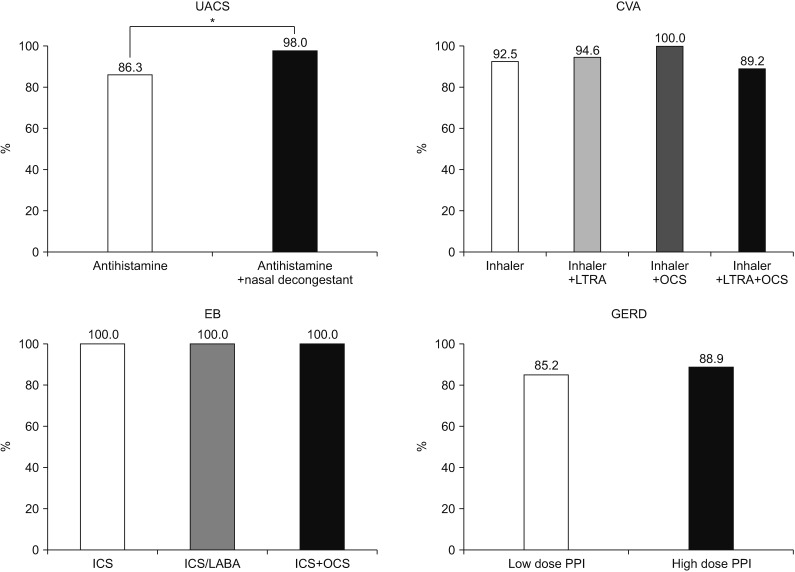

Table 4 summarize the results of subgroup analysis by diagnosis. Tables 5 and 6 summarize the diagnostic methods used and their efficacy in the study participants. Table 7 and Figure 2 describe the treatments used and their outcomes.

Treatment outcomes according to medication. For the treatment of upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), the combination of an antihistamine with a nasal decongestant had a better response than that by treatment with an antihistamine alone (p=0.03). For the treatment of cough-variant asthma (CVA), there was no significant difference in treatment outcome between an inhaler alone, such as inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) or ICS/long-acting β-agonist (LABA), and the combination of an inhaler with leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) or oral corticosteroid (OCS) or LTRA plus OCS. Cough improved in the overall eosinophilic bronchitis (EB) group. There was no significant difference in gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) treatment according to the proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) dose. *Antihistamine vs. antihistamine plus nasal decongestant (p<0.05).

1) UACS

UACS was the most common cause of chronic cough (53.6%). The mean age was 49.1±15.5 years and the mean cough duration was 52.6±127.6 weeks. The UACS group had a higher initial response to treatment than did the non-UACS group (70.5% vs. 55.0%, p=0.002). The response rates after the initial treatment and after 4 weeks of treatment were 70.5% and 89.1%, respectively. A PNS X-ray was performed in most cases (93.9%), of which 29.9% showed abnormal findings. UACS symptoms were found in 93.4% of the subjects. Those were the most highly sensitive marker of UACS. To manage UACS, an antihistamine alone was used most often (66.2%), and a nasal decongestant was combined with the antihistamine in 29.5% of cases. Combination therapy showed a higher response than monotherapy (98.0% vs. 86.3%, p=0.027).

2) CVA

CVA (46.8%) was the second-most common cause of chronic cough. The mean age was 52.1±14.7 years and the mean cough duration was 73.4±185.4 weeks. Those with CVA group were older than those without CVA (52.1±14.7 years vs. 47.4±15.6 years, p=0.001) and showed a higher female predominance (82.5% vs. 68.9%, p=0.001). The response rates after the initial treatment and after 4 weeks of treatment were 64.4% and 93.5%, respectively. BDR tests and methacholine or mannitol bronchial provocation tests (MBPTs) were performed in 87.9% and 91.4% of cases, with positive results in 4% and 47%, respectively. ICS/LABA (88.0%) was selected most often as the treatment and ICS (4.7%) rarely. LTRA (63.5%) and OCS (25.5%) were also used, but there was no clinical benefit of an inhaler combined with LTRA, OCS, or LTRA plus OCS.

3) EB

EB (8.0%) was an uncommon cause of chronic cough among the subjects. The mean age was 47.1±15.1 years. The cough duration was shorter in those with EB group than in those without EB (22.4±26.5 weeks vs. 66.7±182.9 weeks, p<0.001). An initial response to treatment was seen in 57.7% of subjects, and all subjects showed clinical improvement after 4 weeks. Induced sputum test was performed in 61.8% of subjects, and the mean sputum eosinophil percentage was 6.5±10.8%. BDR tests and MBPTs were performed in 44.1% and 85.3% of subjects, respectively, but all results were normal. ICS and ICS/LABA were each used as treatment in 50% of the patients.

4) GERD

GERD (14.8%) was the third most common cause of chronic cough. The mean age was 51.2±15.6 years, and the mean cough duration was 75.5±207.6 weeks. Other clinical characteristics did not differ between those with GERD and those without GERD. Of those with GERD, 53.2% improved after the initial treatment and 88.9% after 4 weeks. GERD was diagnosed based on symptoms in 88.9% of subjects. The treatment response to a low-dose (85.19%) or high-dose (88.89%) PPI did not differ significantly.

5) Other causes and additional evaluations of chronic cough

Overall, 8.7% of the subjects had rare causes of their chronic cough, including psychogenic cough (5.9%), cough hypersensitivity syndrome (0.7%), and idiopathic cough (0.9%). Additional studies were performed in 69.3% of the participants. Allergy skin tests (71.1%) and measurement of immunoglobulin E levels (69.6%) were performed frequently, followed by computed tomography (31.6%). Echocardiography and bronchoscopy (both 0.8%) were performed rarely.

4. Consistency between the initial impression and final diagnosis

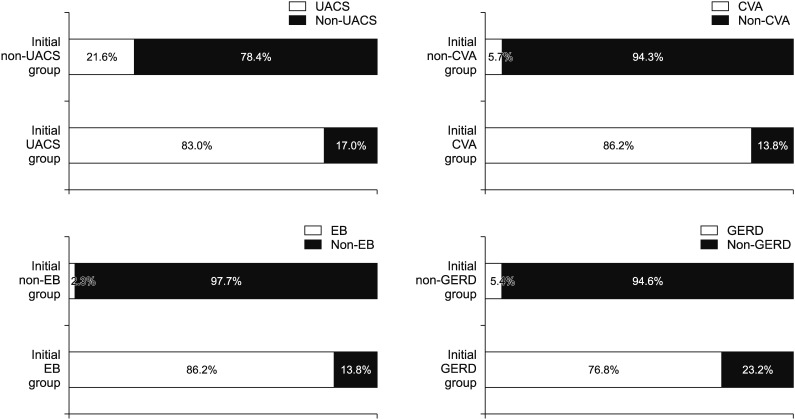

Figure 3 shows the consistencies between the initial impression and final diagnosis. The rates of a consistent initial impression and final diagnosis were high: 83.0%, 86.2%, 86.2%, and 76.8% for those with UACS, CVA, EB, and GERD, respectively. Unlike the other groups, 21.6% of those without an initial impression of UACS were ultimately diagnosed as UACS, and 23.2% of those with an initial impression of GERD were not diagnosed with GERD.

Consistency between the initial impression and final diagnosis of chronic cough. All etiologies showed a high consistency between the initial impression and final diagnosis of chronic cough. Of those with and those without an initial impression of upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), 83% and 21.6%, respectively, were ultimately diagnosed with UACS. The final diagnosis was the same (86.2%) between those with an initial impression of cough-variant asthma (CVA) and those with an initial impression of eosinophilic bronchitis (EB). In contrast, the final diagnosis was not gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) in 23.2% of those with an initial impression of GERD.

5. Factors associated with treatment outcome

Table 8 presents the factors associated with the outcome of chronic cough treatment. In univariate logistic regression analyses, an initial impression of CVA was associated with the treatment response. Those with an initial CVA impression had a 2.51-fold higher treatment response (odds ratio [OR], 2.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.16–5.40), and this factor remained significant in the multivariate logistic regression analysis (OR, 7.06; 95% CI, 1.47–33.81). Other factors including mean age, sex, cough duration, cough NRS baseline score, initial impressions other than CVA, and final diagnosis showed no significance in the univariate or multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Discussion

This retrospective observational study examined the clinical characteristics of chronic cough in Korean adults. Chronic cough in Korean adults was associated with an age in the late forties and a duration of more than 1 year. The mean cough NRS score at baseline was 5.3±1.6 points, which decreased to 1.2±1.4 points after 4 weeks of treatment. UACS and CVA were prevalent causes, whereas GERD and EB were relatively less common. Chronic cough had more than two simultaneous etiologies in 27.4% of the subjects. Following the 2014 KATRD cough-management guidelines, the treatment response was exceptional both after the initial treatment and after 4 weeks. Younger age, longer cough duration, and an initial impression of CVA were factors associated with the treatment responders.

Regarding the diagnostic method for UACS, reporting the symptoms was the most sensitive and accurate method, so determining the precise symptom history is critical for diagnosing UACS. The most common treatment of UACS was an antihistamine alone, but the combination of an antihistamine with a nasal decongestant showed a higher treatment response. Therefore, we should consider this combination for the initial treatment of UACS. Those with UACS showed a greater early treatment response after 1 week compared with those without UACS. The proper treatment duration for UACS needs to be evaluated in the future. Those with CVA were older and more likely to be female than those without CVA. MBPTs showed a higher sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy than those of the BDR test. ICS/LABA was prescribed for most cases, but there were no benefits to the combination of an inhaler with LTRA, OCS, or LTRA plus OCS. Therefore, combination of an inhaler with other treatments should be considered for select cases. Those with EB had a shorter duration of cough, and the sputum eosinophil count did not show sufficient sensitivity or accuracy for diagnosis. Treatment outcomes were not evaluated fully because insufficient cases of EB were enrolled, but all patients with EB showed improvement eventually. The clinical characteristics of those with GERD and those without GERD did not differ significantly, and the treatment response was not affected by the PPI dose. In the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, the only factor that was related to a better treatment response was an initial impression of CVA.

We conducted this study to enhance understanding of the clinical characteristics of chronic cough and the current management situation. In a previous study, chronic cough in Korea was related to male sex, asthma, and chronic rhinosinusitis18. In another study, it was related to smoking, UACS, COPD, and asthma19. Unlike the previous studies, our study excluded smokers and patients with active pulmonary diseases. A strength of this study is that it demonstrated the real-world clinical characteristics of chronic cough in Korea. We found that disease etiologies differ in Korea from other countries. GERD is less prevalent in Korea than in Western countries (10%–40%)20. Asthma was not the most common cause of chronic cough, and GERD was more frequently the cause, in Korea than in Japan212223. These results suggest that regional differences should be considered in the management of chronic cough. We demonstrated the high efficiency of the 2014 KATRD cough-management guidelines in treating Korean adults with chronic cough.

This study has some limitations. First, this study was evaluated retrospectively. However, retrospective nature of this study more truly reflected real-world data of chronic cough than prospective study. Retrospective approach included all patients of chronic cough without selection bias, such as disagreement of study enrollment in prospective setting. Second, the monitoring duration was only 4 weeks. However, patients improved after 4 weeks of treatment mostly (91.2%). This suggests that the proper observation duration is 4 weeks. However, a longer observation study may be required to evaluate the characteristics of the treatment non-responders. Third, because of the study design, rare cases of chronic cough, such as psychogenic cough, cough hypersensitivity syndromes, and idiopathic cough, were diagnosed after 4 four weeks of treatment, and these patients were not monitored or evaluated. However, we included most cases of chronic cough, and these rare cases should be evaluated in a future study of refractory chronic cough.

This was the first study to evaluate chronic cough itself after excluding causes such as smoking or current pulmonary disease. The results provide a better understanding of the various clinical characteristics, diagnostic methods, treatment choices, and treatment outcomes, to aid the management and enhance satisfaction of patients with chronic cough.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Cough research group of the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases.

Notes

Authors' Contributions:

Conceptualization: Yoon HK, Kim HJ, Kim DG.

Methodology: Kim JW, Shin JW, Kim JH, Jung KS.

Formal analysis: An TJ.

Data curation: An TJ, Lee HY, Kang HS, Lee JM.

Software: An TJ.

Investigation: Kim JW.

Date collection: Choi EY, Yoon HK, Jang SH, Kim SK, Kim DG, Rhee CK, Kim YH, Kim JW, Lee SH, Park SY, Kim YH, Moon JY, Yoo KH, Kim DK, Lee H, Koo HK.

Writing — original draft preparation: An TJ.

Writing — review and editing: Kim JW, Rhee CK, Yoon HK.

Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding: This study was supported by the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases.